UPDATE July 2021: 6 years later, there’s a game and also an updated explainer video.

The whole point of egamebook is to allow for complex game worlds that are controlled by a series of simple choices. By simple, I don’t mean “easy” or “without complex consequences”. I just mean they’re not a complicated interface.1 They’re a list of 2 to 5 options to choose from.

More generally, I’m interested in systems that present complex simulations2 in conversational form.

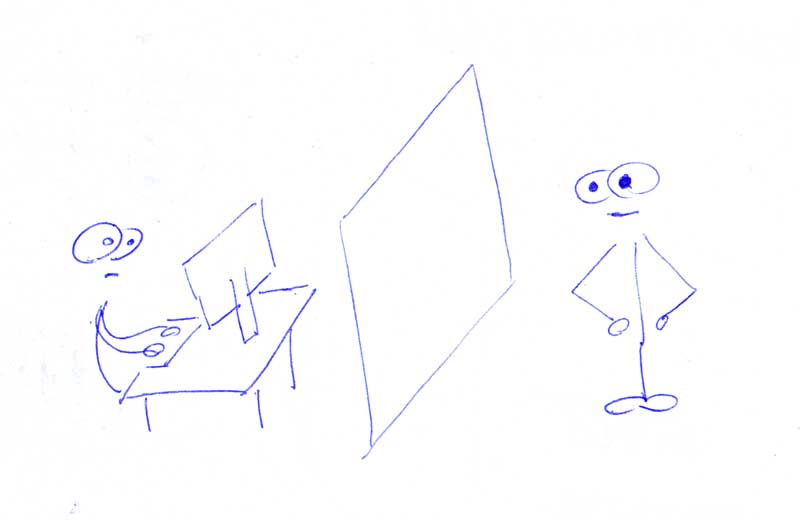

A good way to explain this is to imagine that you’re playing a game through another person. Let’s call this person Interface. You’re sitting behind a curtain while Interface sits in front of the computer and describes to you the situation on the screen. He then gives you options.

If Interface is totally brain dead, he can give you options like “Do you want me to click on this button?” or “Do you want me to move forward one step?” Let’s call these micro-options. They are the lowest level of decisions and you make them a thousand of times per hour. Brain dead Interface would also give you another type of options: dumb options. These would be things like “Do you want to scrap the tank you just built?” or “Do you want to walk into the wall?”

But a person with any amount of intelligence would ask differently. Such Interface would give you options like “Do you want to attack from the north?” or “Do you want to peek into the other room?” I call those real options.

I think we can agree we want computers to give us real options instead of micro-options or dumb options, unless those are unavoidable.

How do you get to real options?

This is obviously the hard part. In traditional gamebooks and interactive fiction, there is almost no simulation, so these options are put there by the authors (i.e. humans). But if you want a more open ended world, what do you do?

The answer is: Artificial Intelligence (AI).

This is again best explained with a game. In games, AI is generally written for the enemies. Some games have allies or wingmen, and those also need AI. In other words, AI is written for all agents in the game except for the player.

But that’s exactly what you want. You want to write your AI in a way that it can be applied to the player. Or, more precisely, to the User Interface (UI).

This is what I tried to do this past weekend when I entered the Ludum Dare #33 competition. (It’s a challenge to create a game in one weekend from scratch, solo.) I used the (still very much incomplete) egamebook library as the engine, and my fuzzy logic library as the basis of the AI. I made a little prototype called Loch Ness.

The game is, of course, very flawed. It does receive quite favorable reviews, but there’s just so much you can do in 2 days, especially if you strive for a strategy game. For me, though, the biggest success is that it only gives you a few options at a time, and they’re not dumb, and you still play in a sandbox world.

The way I did this was simple, really. I wrote the AI code that scores different strategic moves according to their immediate desirability. (For example, moving troops from a well-supplied place to a place where they would starve receives a low score. Attacking an undefended enemy city receives a high score. And so on.) In traditional AI fashion, this code is then used by the opposing factions3 by scoring all possible moves and then picking the most desirable ones.

But — since I already have a mechanism to score moves — I can use the same thing for the player. I score all the possibilities, sort them, then pick the first few and bring them up as options.4

This makes sure that you don’t need to pick from 100 or more options,5 most of which are irrelevant or dumb. But it still gives you the freedom of a simulated world.

But what about surprising choices?

If you preselect options programmatically, you’ll prevent the player/user from making surprising decisions, right? It’s like railroading,6 right?

I don’t think so.

First of all, yes, you’ll prevent things like shooting yourself in the foot. Things that are obviously dumb. People sometimes want to do those7 but they get bored by them very quickly.

The really surprising and innovative things people do in games (and elsewhere) are seldom on a single action level. They are strings of non-dumb actions.

To make yet another gaming example: in a game like Civilization, you can let a city starve for no reason — that’s innovative in a sense, but probably not the kind of innovative or emergent gameplay most game developers strive for.8 On the other hand, if you invest heavily in technology, then sell that technology to others, and finance a space ship from that money, then you haven’t done any dumb move along the way, but you did something interesting and maybe unexpected.

In short, it’s up to the player what to do in the game world as long as it’s not obviously dumb.

To be sure, there are still valid options that may seem dumb for the AI but that are actually clever.9 What I’m saying is that those are scarce exceptions. Most creative gameplay stems from choices that are not dumb, they’re just orchestrated in an inspired way.

So?

I am extremely excited about this, especially since now that I have a prototype (Loch Ness) that kind of proves it’s realistic, not just a pipe dream.

For games and interactive storytelling, I hope this means we can have complex game worlds with many options, but in a gamebook form, without the need of overly complicated UI. I’m not saying I only want those. I still love to play games like Civilization, of course. But I also want those complex egamebooks to exist.

There are implications outside games, too. Think about an eshop that intelligently walks you through the checkout process (I made a prototype of that recently). Think about an app that’s easier to use. Think about a learning tool that lets you explore the subject in a way that’s not overwhelming.

Thanks for reading this far. Let me know what you think.

UPDATE July 2021: 6 years later, there’s a game and also an updated explainer video.

-

You could say that even strategic games like Civilization only present a few buttons at a time. But you’re forgetting the world map where each of the thousands of tiles is a potential option. ↩

-

Almost all games are simulations. Super Mario or Pac-Man are simulated worlds, although very simple. ↩

-

In the Ludum Dare version of the game, there is just one opposing faction: the humans. But if I get to move the game forward, it’ll be easy for me to add others. Also, the same code can be used for monsters (something like captains) inside the player faction, so the player can delegate. ↩

-

Actually, the algorithm of choosing the options to show is a bit more involved. To ensure that there’s always variety, the algorithm makes sure that there are no more than three options of the same type. So even if the AI things the 5 most desirable actions for the player right now are to attack (the only thing changing is the city), then we only choose the 3 most desirable ones, but also give the player other types of options: laying eggs, moving, and so on. ↩

-

Move unit A to location α, move unit A to location β, … move unit Z to location ω. ↩

-

Railroading is the term used when a game keeps you from doing what you want and leads you in an overly linear fashion. TV Tropes has a good article about it, as usual. ↩

-

Think games like Grand Theft Auto, where almost any player has tried at least once to do something self-destructive. ↩

-

I’m sure some Civilization players out there have done it, but probably not more than once. ↩

-

The rocket jump is a good example. ↩